WHAT YOU NEED TO GET STARTED

Lesson Videos

- Available on DVD, as digital downloads, and streamed as an individual subscription or as part of the Compass Classroom Membership

- 26 lessons with 5 videos each; additional videos explain the quarterly projects

Student Reader

- Available as digital files with your purchase, or as a separate download or printed book (over 300 pages)

- Includes daily readings, assignments, and weekly exams.

Portfolio

- Essentially a scrapbook or a visual textbook for the semester’s lessons which shows the lessons that have been verbally discussed.

- Provided by the student: a scrapbook, photo album, 3-ring binder, or a fine sketchbook of durable quality such as card stock or a heavy drawing paper.

Teacher’s Guide

- Scope & Sequence for two semesters of Middle/High School (Ages 13+)

- Portfolio & Project Guide

- Grading Guides for Exams, Readings, the Portfolio, and Projects

- Suggested Titles for Further Reading to go along with all 26 Lessons

- Exam Answer Key

Supplementary Audio Products

Need help organizing the digital curriculum? We’ve got a helpful entry on our blog that covers just that!

HOW DAVE RAYMOND’S AMERICAN HISTORY WORKS

There are a number of different elements to this curriculum that make it quite unique.

Once you see how everything works together, however, it should be fairly easy to teach.

The class is designed to fill two semesters. It covers 26 Lessons with the goal of completing one Lesson per week. Each Lesson is broken down into five different lectures (approximately 10 minutes each) with associated readings or assignments.

Each day, plan on scheduling approx. 10 minutes for the video and 10 minutes for the daily reading and questions.

Each week, budget approximately 20 minutes for the exam, and another 20 for the Lesson’s Portfolio entry. These elements can be modified to suit the age and frame of your student. For example, parents of middle school students might remove the daily readings to concentrate on the Portfolio, and integrate the Exam questions as a summary of the applicable lesson video.

You can assign one lecture a day or you can go through two or more lectures in one day. Your student will be the best gauge as to how much he or she can effectively cover at one time.

One Lesson is normally completed per week. Use the included chart (sample) to mark off what has been finished. Only exams, essays and projects are scored.

If an Assignment asks one or more questions, these are meant to be considered by the student as he or she does the reading. You can also use these questions as a way to discuss the lesson with your student after the lesson and readings are complete.

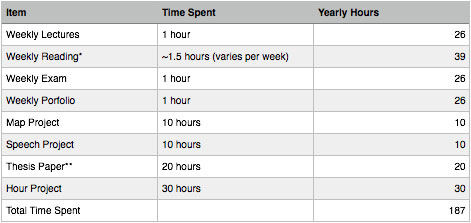

CALCULATING HIGH SCHOOL CREDIT FOR HISTORY

HSLDA recommends spending approximately 150 hours on a subject to qualify for high school credit.

This is how Dave Raymond’s classes generally break down to achieve that credit. Some students will spend more time in some areas and some will spend less, but there is clearly enough different types of work to qualify for full high school credit.

The reader includes 372 pages of original historical materials. It increases in length as the year progresses. For example, Lessons in the first semester comprise 150 pages while those in the second comprise 222 pages. If additional reading is desired for older students, we include recommendations for that.

If a parent desires to do two or more thesis papers for older students, that is perfectly acceptable and will only increase the amount of time spent in the class.

Suggested Titles for Further Reading

In Order of Lessons

Lessons 1 & 2

- Theodore Roosevelt’s History of the United States, selected and arranged by Daniel Ruddy

Lesson 3

- A New World in View by Fred Young, Gary DeMar, and Jane Scott

- The Log of Christopher Columbus by Robert Fuson

Lesson 4

- A New World in View by Fred Young, Gary DeMar, and Jane Scott

- A History of the American People by Paul Johnson (Selections from this hefty tome are great for multiple lessons.)

Lesson 5

- Of Plymouth Plantation by William Bradford

- Punic Wars and Culture Wars: Christian Essays on History and Teaching by Ben House

Lesson 6

- Worldly Saints: The Puritans as They Really Were by Leland Ryken

Lesson 7

- The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper

Lesson 8

- The Sermons of Jonathan Edwards: A Reader, selected by Wilson Kimnach, Kenneth Minkema, and Douglas Sweeney

Lesson 9

- Samuel Adams by James Kendell Hosmer

- The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

- John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic by Jeffry Morrison

- Patrick Henry by Moses Coit Tyler

Lesson 10

- 1776 by David McCullough

- Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer

Lessons 11 & 12

- Hero Tales from American History by Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt

- History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution by Mercy Otis Warren

- The Boys of ’76: A History of the Battles of the American Revolution by Charles Carleton Coffin

Lesson 13

- Christianity and the Constitution by John Eidsmoe

Lesson 14

- George Washington: The Founding Father by Paul Johnson

Lesson 15

- The Adams-Jefferson Letters edited by Lester J. Cappon (An abridged version edited by Paul Wilstach is available used.)

Lesson 16

- The Winning of the West by Theodore Roosevelt

- Democracy in America by Alexis DeTocqueville, abridged and edited by Richard D. Heffner

Lesson 17

- The Tennessee, Volume One, The Old River: Frontier to Secession by Donald Davidson

Lesson 18

- A History of the American People by Paul Johnson

Lesson 19

- A Theological Interpretation of American History by Gregg Singer

- Bible in Pocket, Gun in Hand: The Story of Frontier Religion by Ross Phares

Lesson 20

- The Causes of the Civil War, edited by Kenneth Stampp

- Mighty Rough Times, I Tell You, edited by Andrea Sutcliffe

Lesson 21

- Lincoln’s Battle With God by Stephen Mansfield

Lessons 22 & 23

- The Civil War: A Narrative by Shelby Foote

- Christ in the Camp by J. William Jones

- Best Littler Stories From the Civil War by C. Brian Kelly with Ingrid Smyer

- The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara

Lesson 24

- The Legacy of the Civil War by Robert Penn Warren

Lesson 25

- Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and The American West by Dee Brown

- A History of the American People by Paul Johnson

Lesson 26

- Carry a Big Stick: The Uncommon Heroism of Theodore Roosevelt by George Grant

- Then Darkness Fled: The Liberating Wisdom of Booker T. Washington by Stephen Mansfield

- Up From Slavery by Booker T. Washington