WHAT YOU NEED TO GET STARTED

Lesson Videos

- Available on USB stick, as digital downloads, or as part of the Compass Membership

- 26 lessons with 5 videos each; additional videos explain the three project

Student Reader

- Available as digital files with your purchase, or as a separate download or printed book (226 pages).

- Includes daily readings, assignments, and weekly exams.

Portfolio

- Essentially a scrapbook or a visual textbook for the semester’s lessons which shows the lessons that have been verbally discussed.

- Provided by the student: a scrapbook, photo album, 3-ring binder, or a fine sketchbook of durable quality such as card stock or a heavy drawing paper.

Teacher’s Guide

- Scope & Sequence for two semesters of High School (Ages 14+)

- Portfolio & Project Guide

- Grading Guides for Exams, Readings, the Portfolio, and Projects

- Suggested Titles for Further Reading to go along with Lessons

- Answer Key to reading prompts in the Student Reader

- Exam Answer Key

Need help organizing the digital curriculum? We’ve got a helpful entry on our blog that covers just that!

HOW DAVE RAYMOND’S CHRISTENDOM WORKS

There are a number of different elements to this curriculum that make it quite unique.

Once you see how everything works together, however, it should be fairly easy to teach. You will also want to watch all five parts of Lesson 1 – Orientation. The entire curriculum is explained in detail there.

The class is designed to fill two semesters. It covers 26 Lessons with the goal of completing one Lesson per week. Each Lesson is broken down into five different lectures (approximately 15-20 minutes each) with associated readings or assignments.

Each day, plan on scheduling approx. 20 minutes for the video and 15 minutes for the daily reading and questions.

Each week, budget approximately 20 minutes for the exam, and another 20 for the Lesson’s Portfolio entry. These elements can be modified to suit the age and frame of your student. For example, parents of middle school students might remove the daily readings to concentrate on the Portfolio, and integrate the Exam questions as a summary of the applicable lesson video.

You can assign one lecture a day or you can go through two or more lectures in one day. Your student will be the best gauge as to how much he or she can effectively cover at one time.

The readings in the second semester of this series are often longer than the readings in the first half. As the teacher, feel free to abridge any of the writings to more appropriately challenge your student.

One Lesson is normally completed per week. Use the included chart (sample) to mark off what has been finished. Only exams, essays and projects are scored.

If an Assignment asks one or more questions, these are meant to be considered by the student as he or she does the reading. You can also use these questions as a way to discuss the lesson with your student after the lesson and readings are complete.

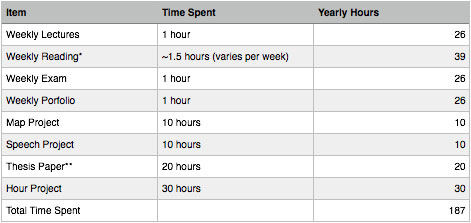

CALCULATING HIGH SCHOOL CREDIT FOR HISTORY

HSLDA recommends spending approximately 150 hours on a subject to qualify for high school credit.

This is how Dave Raymond’s classes generally break down to achieve that credit. Some students will spend more time in some areas and some will spend less, but there is clearly enough different types of work to qualify for full high school credit.

The reader includes over 220 pages of original historical materials. It increases in length as the year progresses. For example, Lessons in the first semester comprise approximately 90 pages while those in the second comprise approximately 130 pages. If additional reading is desired for older students, we include recommendations for that.

If a parent desires to do two or more thesis papers for older students, that is perfectly acceptable and will only increase the amount of time spent in the class.

Suggested Titles for Further Reading

Corresponding roughly to the chronology of the course

- An Experiment in Criticism by C.S. Lewis

- The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm translated by Jack Zipes

- Acts of the Apostles

- Epistles of Paul (selections)

- Confessions by Augustine, translated by Maria Boulding

- The Rule of St. Benedict translated by Timothy Fry

- Beowulf translated by Seamus Heaney

- The Song of Roland translated by Dorothy Sayers

- The Oxford Book of English Verse, edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch (1250-1918)

- Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott

- The Divine Comedy by Dante, translated by Dorothy Sayers

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight translated by J.R.R. Tolkien

- The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, translated by Nevill Coghill

- King Arthur and His Knights: Selected Tales by Sir Thomas Malory, edited by Eugene Vinaver

- The Golden Booklet of the True Christian Life by John Calvin, translated by Henry J. Van Andel

- Institutes of the Christian Religion by John Calvin (selections)

- Fierce Wars and Faithful Loves: Book I of the Faerie Queen by E. Spenser, edited by R. Maynard

- Macbeth by William Shakespeare (Oxford School Shakespeare edition)

- Hamlet by William Shakespeare (Oxford School Shakespeare edition)

- Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan